Egypt is a land rich in gold, and ancient miners employing traditional methods were thorough in their exploitation of economically feasible sources. In addition to the resources of the Eastern Desert, Egypt had access to the riches of Nubia, which is reflected in its ancient name, nbw (the Egyptian word for gold). The hieroglyph for gold—a broad collar—appears with the beginning of writing in Dynasty 1, but the earliest surviving gold artifacts date to the preliterate days of the fourth millennium B.C.; these are mostly beads and other modest items used for personal adornment. Gold jewelry intended for daily life or use in temple or funerary ritual continued to be produced throughout Egypt’s long history.

The gold used by the Egyptians generally contains silver, often in substantial amounts, and it appears that for most of Egypt’s history gold was not refined to increase its purity. The color of a metal is affected by its composition: gradations in hue that range between the bright yellow of a central boss that once embellished a vessel dating to the Third Intermediate Period and the paler grayish yellow of a Middle Kingdom uraeus pendant are due to the natural presence of lesser or greater amounts of silver.

In fact, the pendant contains gold and silver in nearly equal amounts and is therefore electrum, a natural alloy of gold containing more than 20 percent silver, as defined by the ancient Roman author, naturalist, philosopher, and historian Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis historia.

A ring dated to the Amarna Period depicting Shu and Tefnut illustrates a rare occasion when an Egyptian goldsmith added a significant amount of copper to a natural gold-silver alloy to attain a reddish hue.

The survival of gold artifacts is skewed by accidents of history and excavation; Egyptian sites have been looted since ancient times, and much precious metal was melted down long ago. Overall, relatively few gold pieces survive from the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods, which are represented in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection by a small bangle bracelet from the tomb of Khasekhemwy, the last ruler of Dynasty 2. It was made from a broad band of hammered gold sheet. Small stone vessels that had been sealed with hammered sheets of gold textured to resemble animal hide and tied down with gold wire “string” were also found in the royal tomb.

Malleability, a physical property shared by many metals and most pronounced for gold, is the ability to be hammered into thin sheets, and it is in this form that most gold artifacts from ancient Egypt survive: solid, cast gold objects, such as a ram’s-head amulet dated to the Kushite Period, are generally small and relatively rare.

Gold leaf as thin as one micron was produced even in ancient times, and thicker foils or sheets were applied mechanically or with an adhesive to impart a golden surface to a broad range of other materials, including the wood of Hapiankhtifi’s model broad collar dating to Dynasty 12, and the bronze mount of a basalt heart scarab dating to the New Kingdom.

On the broad collar, the leaf was applied onto a layer of gesso (plaster with an adhesive gum) over linen; on the scarab, a somewhat thicker foil was crimped between the bronze mount and the stone scarab. Gold inlays were also used to enhance works in other media, especially bronze statuary.

During Ptolemaic and Roman times, gilded glass jewelry was popular in Egypt. A fusion process for gilding silver was developed in the Near East, most likely in Iran. Its probable use in Egypt during the late first millennium B.C. has not yet been well studied; during the Roman Period, mercury gilding, an import from East Asia, became the most common process for gilding silver or cupreous substrates used in the Mediterranean world, and it remained so into early modern times.

Excavations at Dahshur, Lahun, and Hawara in the early twentieth century unearthed much jewelry that belonged to elite women associated with the royal courts of the Dynasty 12 kings Senwosret II and Amenemhat III. Sithathoryunet’s pectoral was made using the cloisonné inlay technique: scores of hammered gold strips known as cloisons, a French word for partitions, form cells on the gold back plate assembled from multiple hammered sheets and several cast elements. The reverse of the back plate was elegantly scored with the same patterns and additional details. The pectoral certainly was valued for its exquisite form and execution, but its function was primarily ritual: inscribed with the name of Senwosret II, it reflects Sithathoryunet’s role in assuring his well-being throughout eternity.

Although gold as a commodity appears to have been largely controlled by the king, Egyptians of less than royal status also owned gold jewelry: Middle Kingdom cylinder amulets often feature granulation, a technique for adding details and creating relief using small metal spheres (granules), here arranged in zigzags. The granules were generally attached using a method known as colloidal hard soldering, which relies on the chemical reduction of a finely ground copper-mineral powder that locally lowers the melting point of adjacent gold surfaces. The ensuing diffusion of gold and copper atoms between the surfaces of the granules and the hammered sheet support creates a physical bond.

Another important method used to join precious metals in antiquity and in modern times is soldering. In order to carry out this process, an alloy—e.g., the solder—is formulated so as to have a lower melting point than the metals it is intended to join. The solder is hammered into a sheet and cut into minute squares or strips known as paillons. Once placed in strategic locations, the paillons are heated, so that they melt and locally reduce the melting point of adjacent gold surfaces, thereby facilitating diffusion of the molecules between the solder and the components to be joined. A primitive form of soldering has been observed on an early Dynasty 12 gold ball-bead necklace found on the mummy of Wah, and more accomplished work can be observed on the electrum uraeus pendant.

The staggering amount of gold found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, the only ancient Egyptian royal burial to have been found in a relatively intact state, illustrates almost unfathomable wealth, but Egyptologists suspect that the kings who ruled into middle or old age were accompanied into the next life with even more numerous luxury goods. Far less important members of New Kingdom royal families were also interred with lavish gold treasures.

Three foreign women known to have been minor wives of Thutmose III were interred together with similar assemblages of gold jewelry and various funerary articles. For example, each queen had a pair of gold sandals made of hammered gold sheet with scored decoration on the insole, and cosmetic vessels made from an assortment of stones and other materials fitted with gold sheet.

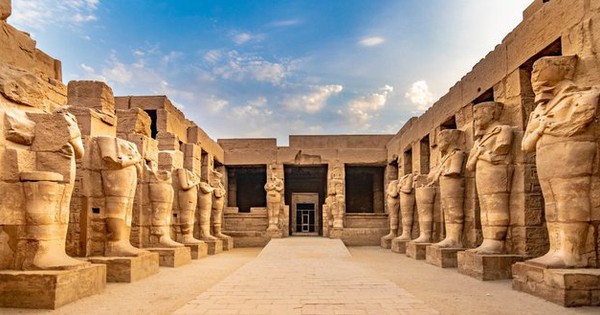

Ancient texts report the vast quantities of statuary of gold, silver, bronze, and other metals that were used in Egyptian temple ritual, but of these only a single gold statue is known to survive. The body of this figure of Amun, minus the arms, was solid cast in a single piece, and the separately cast arms were soldered in place. His regalia was also produced separately: in his right hand he holds a scimitar, in the left an ankh sign, the latter made of numerous components joined using solder. It has been suggested, on technical grounds, that the absence of Amun’s crown, a triple attachment loop, and the statue’s support, each also made separately and originally soldered in place, do not represent ancient damages or the effects of burial, but were removed before the statue was acquired for the Carnarvon Collection in 1917.

Wire technology is an essential part of goldworking, especially for jewelry. For example, wires were used to produce surface decoration, often in conjunction with granulation work, and they were applied using the same colloidal hard soldering method. The wires could be twisted, braided, or woven to make chains, and then used structurally to join individual components. The wires themselves were made from tightly twisted metal strips or rods or from square section rods that were hammered to attain roundness. The yards of wire that make up the strap chain fragment were produced using the former method; the wires on the electrum uraeus pendant were hammered.

In Macedonian, Ptolemaic, and Roman times, jewelry made elsewhere circulated in Egypt, and local production reflects these and other foreign influences. One foreign practice in jewelry design introduced into Egypt during the Roman Period was the incorporation of gold coins—the Egyptian economy was commodity-based until about the time of Alexander the Great—along with the pierced settings framing the coins, which were produced by a typically Roman technique known as opus interassile.