A cave that the ancient Romans believed was the gateway to hell, so deadly that it killed all animals that came near, but at the same time left the priests who guided them unharmed.

Millennia later, scientists believe they have figured out why – a dense cloud of carbon dioxide suffocates animals that breathe it.

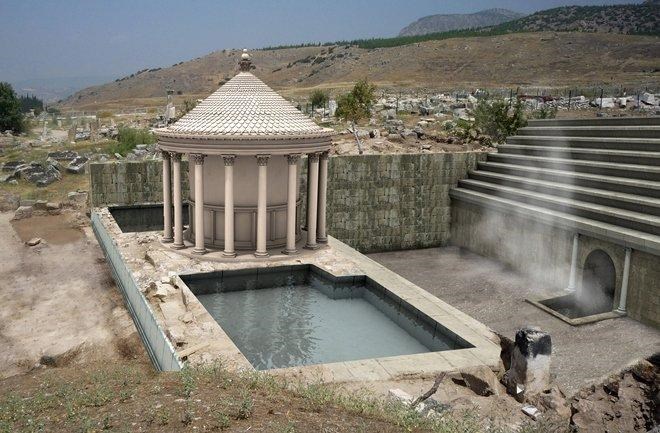

Dating back 2,200 years, the cave was rediscovered by archaeologists from the University of Salento in 2011.

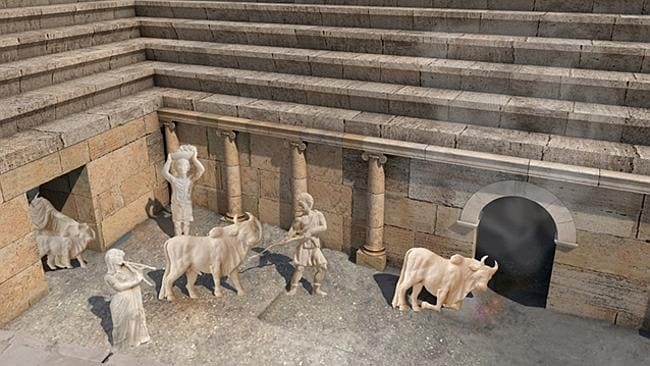

Plutonium simulation image

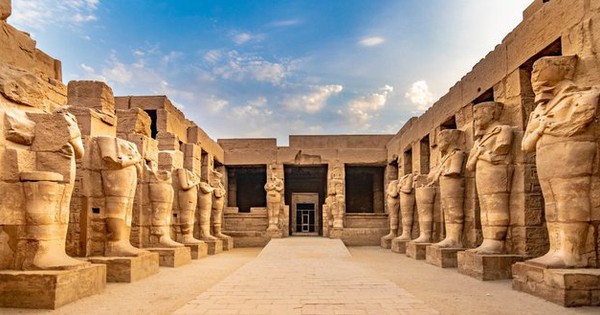

It was located in a city called Hierapolis in ancient Phrygia, now Türkiye, and was used for animal sacrifices, which were bulls led through the Plutonium, or Gate of Pluto, the ancient god of the underworld – by celibate priests.

The purified priests are sacrificing bulls.

As the priests led the bulls in, people could sit on high chairs above and watch the smoke billow from the gate causing the animals to die.

“ This space was so full of fog and so thick that one could hardly see the ground. Any animal that entered it met instant death. I threw sparrows in and they immediately breathed their last and fell down. ” The Greek historian Strabo (64 BC – 24 AD) wrote.

A photo shows dead birds at the entrance to the “Gateway to Hell”

It was this phenomenon that alerted the archaeological team to the cave’s location. Birds that flew too close to the cave’s entrance suffocated and fell in – suggesting that, thousands of years later, it was still as deadly as ever.

The culprit is underground seismic activity, according to volcanologist Hardy Pfanz of the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany, who led a 2018 study of the cave’s gas. A fissure running deep beneath the area releases large amounts of volcanic carbon dioxide.

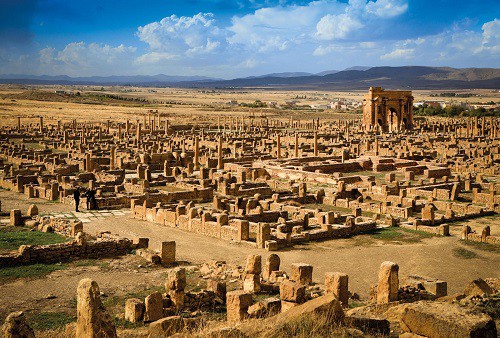

The Current Status of Plutonium

The team measured carbon dioxide levels in the area connected to the cave, and found that the gas – which is slightly heavier than air – formed a layer 40 centimeters (15.75 inches) above the floor.

They found that the gas was dispersed by the Sun during the day, but was most dangerous at dawn after a night of accumulation. Concentrations reached over 50% at the bottom of the lake, about 35% at a height of 10cm, which could kill a person – but, above 40cm, concentrations dropped rapidly.

During the day, there is still some carbon dioxide about 5 centimeters high, as evidenced by dead bugs the team found on the floor of the area. And inside the cave, they estimate that CO2 concentrations consistently hover between 86 and 91 percent, since neither the Sun nor the wind can get in.

An inscription at the site refers to the underworld gods Pluto and Kore. (Francesco D’Andria / University of Salento)

The researchers note in their paper that there is a strong tourist element to the site. Tourists can buy small animals and birds that they can throw down as sacrifices, and on holidays, larger animals are sacrificed by priests.

“While the bull stood in the gas lake with its mouth and nostrils 60 to 90 centimeters high, the large, adult priests (galli) always stood upright in the lake, ” the team wrote in their 2018 paper.

The spectators would see the huge, strong bulls succumb to the smoke within minutes, while the priests remained strong and proud – a testament to the power the gods and priests had to show to the people at that time.

However, researchers believe that the priests were well aware of the properties of the cave and the surrounding arena area, and may have conducted large sacrifices at dawn or dusk on quiet days to achieve maximum effect.

Current status of the area today

They may also stick their heads inside or into caves during noon ceremonies to demonstrate their abilities, holding their breath to endure.

But the presence of oil lamps also suggests that priests approached the cave at night, according to the researcher who discovered it, Francesco D’Andria.

Today the ancient city of Hierapolis remains a popular tourist attraction for thousands of visitors.